“A Christmas Story” was anything but an instant classic. Released on Nov. 18, 1983, the movie wasn’t even booked in theaters during that Christmas season. But when it caught on a few years later—thanks to the emergence of VHS and gradual air time on major cable networks—the low-budget film stuck like tongue to metal on a bully of a winter’s day.

Today, TBS annually shows “A Christmas Story” for 24 straight hours beginning on Christmas Eve; the movie has its own museum. Jean Shepherd never stuck in the national consciousness to the same degree, even though the movie is based on vignettes from his short story collection “In God We Trust, All Others Pay Cash.” Even though Shepherd is the film’s narrator and made a cameo appearance. Even though he wrote best-selling books, has been compared to Will Rogers as a storyteller, and starred in two television series. Even though he was a radio host on New York’s WOR-AM from 1955 to 1977 who attracted a passionate following with his flair for daring, creative routines that made storytelling urban hip—earning him a berth in the National Radio Hall of Fame. Even though he is the inventor of one of the most iconic props in film history: the leg lamp.

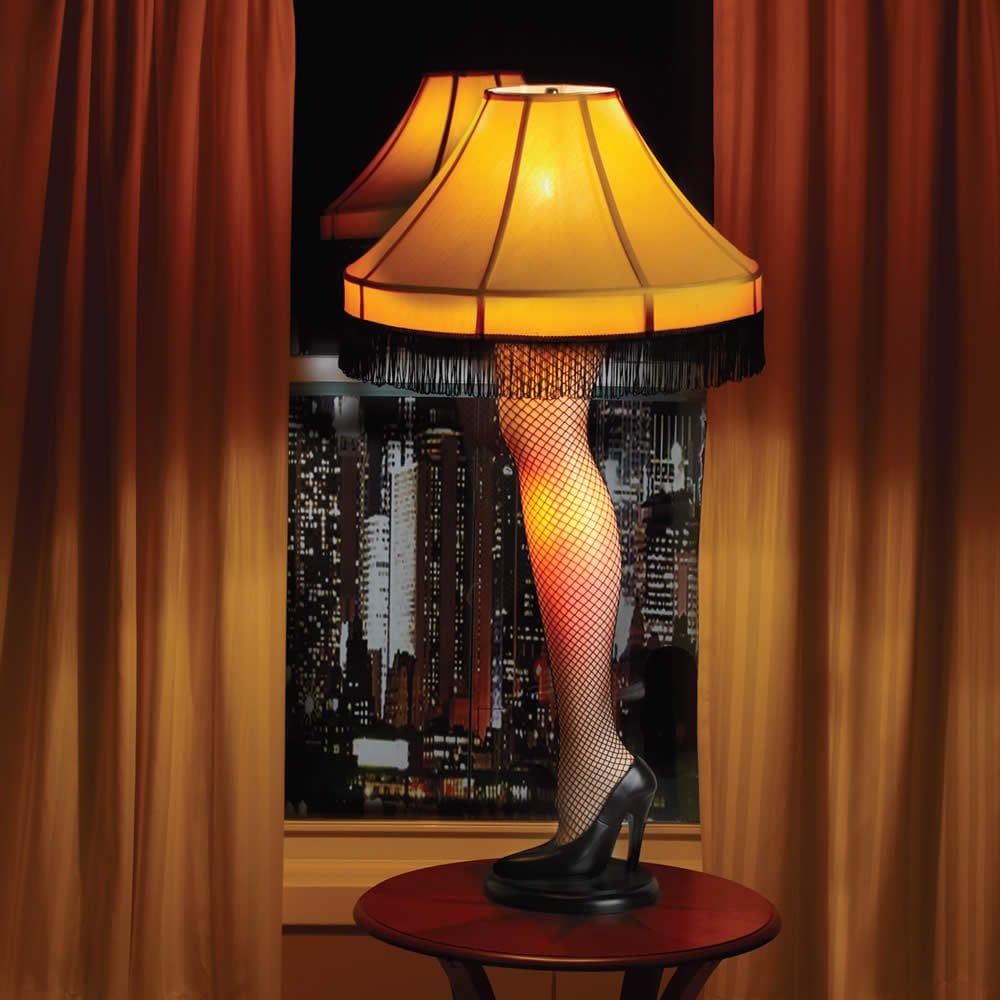

Old Man Parker’s “major award” for winning a crossword contest in the movie was conceived by Shepherd in a 1966 short story, “My Old Man and the Lascivious Special Award That Heralded the Birth of Pop Art.” Shepherd said it was inspired by Nehi (pronounced knee-high) soda ads showing two shapely legs up to the knee that he remembered as a boy; his description of the bizarre appliance underscored his fertile imagination and writing prowess.

“From ankle to thigh the translucent flesh radiated a vibrant, sensual, luminous orange-yellow-pinkish nimbus of Pagan fire,” he wrote. ”All it needed was tom-toms and maybe a gong or two. And a tenor singing in a high, quavery, earnest voice: ‘A pretty girl /Is like a melody …’”

Reuben Freed, the production designer for “A Christmas Story,” told Cleveland magazine in 2009: “I immediately thought of something I had seen in my mother’s front room, which was sort of a gold-colored silk lampshade, pleated with fringe around it. I thought of it immediately and never thought of anything else—just that classic, big ugly shape.” He reportedly drew a couple of quick sketches that Shepherd approved immediately.

From an intellectual property standpoint, the leg lamp is as strong as it is shapely: protected by a federal trademark registration (U.S. Registration No. 3,364,542). Ditto for an accompanying leg lamp ornament (U.S. Registration No. 3,367,925). So although Shepherd was not an inventor per se, his uniquely creative intellect registered with many and had the ideal vehicle via the media explosion of the mid-20th century.

Brilliant enigma

Shepherd, who died in 1999, never expressed frustration that some “A Christmas Story” devotees don’t know who he was. But he was reportedly critical of some actors during filming—he had 17 acting credits—even suggesting they weren’t doing it right. Perhaps fittingly, his cameo in the movie is that of an angry man who directs Ralphie to the back of the Santa Claus line in a department store.

It may be simplistic, even inaccurate, to characterize him as angry. Shepherd’s radio listeners and readers remember the enigmatic genius as jaded, cynical and fatalistic, yet alternately hopeful, funny and appreciative of America’s beauty. Among his written and spoken gems:

“The hand of fate had dipped into the ragbag of humanity.”

“The truth will always have a market.”

“Can you imagine 4,000 years passing, and you’re not even a memory? Think about it, friends. It’s not just a possibility. It is a certainty.”

“In all my years of New York cab riding, I have yet to find the colorful, philosophical cab driver that keeps popping up on the late movies.”

His radio show spawned a Pied Piper following. Shepherd had an uncanny ability to spin seemingly impromptu yarns about his darkly colorful childhood in Hammond, Indiana; his three years in the Army during World War II; postwar radio and TV jobs ranging from host to engineer to sportscaster; and his insights on modern society.

Donald Fagen, cofounder of the group Steely Dan who was a rabid listener while growing up in New Jersey, recalled on slate.com: “He’d sing along to noisy old records, play the kazoo and the nose flute, brutally sabotage the commercials, and get his listeners—the ‘night people,’ the ‘gang’—to help him pull goofy public pranks on the unwitting squares that populated most of Manhattan. In one famous experiment in the power of hype, Shepherd asked his listeners to go to bookstores and make requests for ‘I, Libertine,’ a nonexistent novel by a nonexistent author, Frederick R. Ewing. The hoax quickly snowballed and several weeks later ‘I, Libertine,’ was on best-seller lists.”

Shepherd had the ability to leave a mark on people who weren’t like him, people who didn’t like him, people from all walks of life. Comedian Jerry Seinfeld, who named his third child Shepherd, once said: “He really formed my entire comedic sensibility. I learned how to do comedy from Jean Shepherd.” Bill Griffith, writer of the “Zippy” comic strip, has said Shepherd was an inspiration for “plucking random memories from my childhood.”

‘He told you what to expect’

The Shepherd phenomenon was so much more than Will Rogers Meets “Wayne’s World.” His depth of intellect and understanding revealed a highly sophisticated mind and the internal complications that often result. Wrote Fagen:

“I learned about social observation and human types: how to parse modern rituals (like dating and sports); the omnipresence of hierarchy; joy in struggle; “slobism”; “creeping meatballism”; 19th-century panoramic painting; the primitive, violent nature of man; Nelson Algren, Brecht, Beckett, the fables of George Ade; the nature of the soul; the codes inherent in ‘trivia,’ bliss in art; fishing for crappies; and the transience of desire. He told you what to expect from life (loss and betrayal) and made you feel that you were not alone.”

After Shepherd left WOR in 1977, he worked with director Bob Clark on “A Christmas Story,” had a successful career on public television and performed onstage. But according to some observers, his narcissism became more pronounced, his quirks less palatable. Fagen wrote that Shepherd became paranoid; was dismissive of all of his radio work; insisted that all of his childhood stories were made up, and even made fun of his longtime fans. “To borrow his favorite slur, Jean Shepherd had become a fathead,” wrote The Atlantic.

Although Shepherd voices an adult Ralphie in the movie, he may have been more like Old Man Parker: guarded, cantankerous and fra-GEE-lay, unwilling or unable to shed the mask he admittedly wore, someone who may not be a memory in 4,000 years but someone whose impact will be felt for a long time.

We double-dog dare you to top these fun leg lamp facts:

- Three leg lamps were made for the movie, but none of them exist today. Despite reports that none of the three survived the filming, the Canadian blog Retrofestive says one lamp sat for years in the window of Martin Malivoire’s special-effects shop in Toronto. It became dirty and dusty, and was discarded in the early 1990s.

- The lamp was created by casting a mold of a woman’s leg.

- The label “His End Up” on the crate that contained the leg lamp in the movie wasn’t meant to be a joke. Jim Moralevitz, who played one of the leg-lamp delivery men, told the Cleveland News-Herald that “the crate was so wide that it wouldn’t fit through the door. So they called in the carpenters and they took four inches off.”

- You probably have seen current-day leg lamps for sale, but you may not know they’ve been available since 2003. Memorabilia company NECA was the first to license and mass-produce them.

- Because much of the movie was filmed in Cleveland, Terminal Tower in Cleveland’s Public Square was turned into a giant leg lamp—complete with a red garter—to celebrate the movie’s 30th anniversary in 2013.

There is a lot of misinformation surrounding the real Shepherd out in the public domain. For example, he actually served in uniform for only 20 months, not three years as stated in the article. And a real Leg Lamp — having nothing to do with Shep or his Old Man — was available for sale by spring 1950. It cost as little as $7.50, including white or pink lamp shade, and that was for 2 “provocative” legs, not one! It was over 19 inches of electric sex with “approved wiring” . . . .